Biceps Tendon Ruptures

Biceps Tendon Ruptures

Anatomy and Function

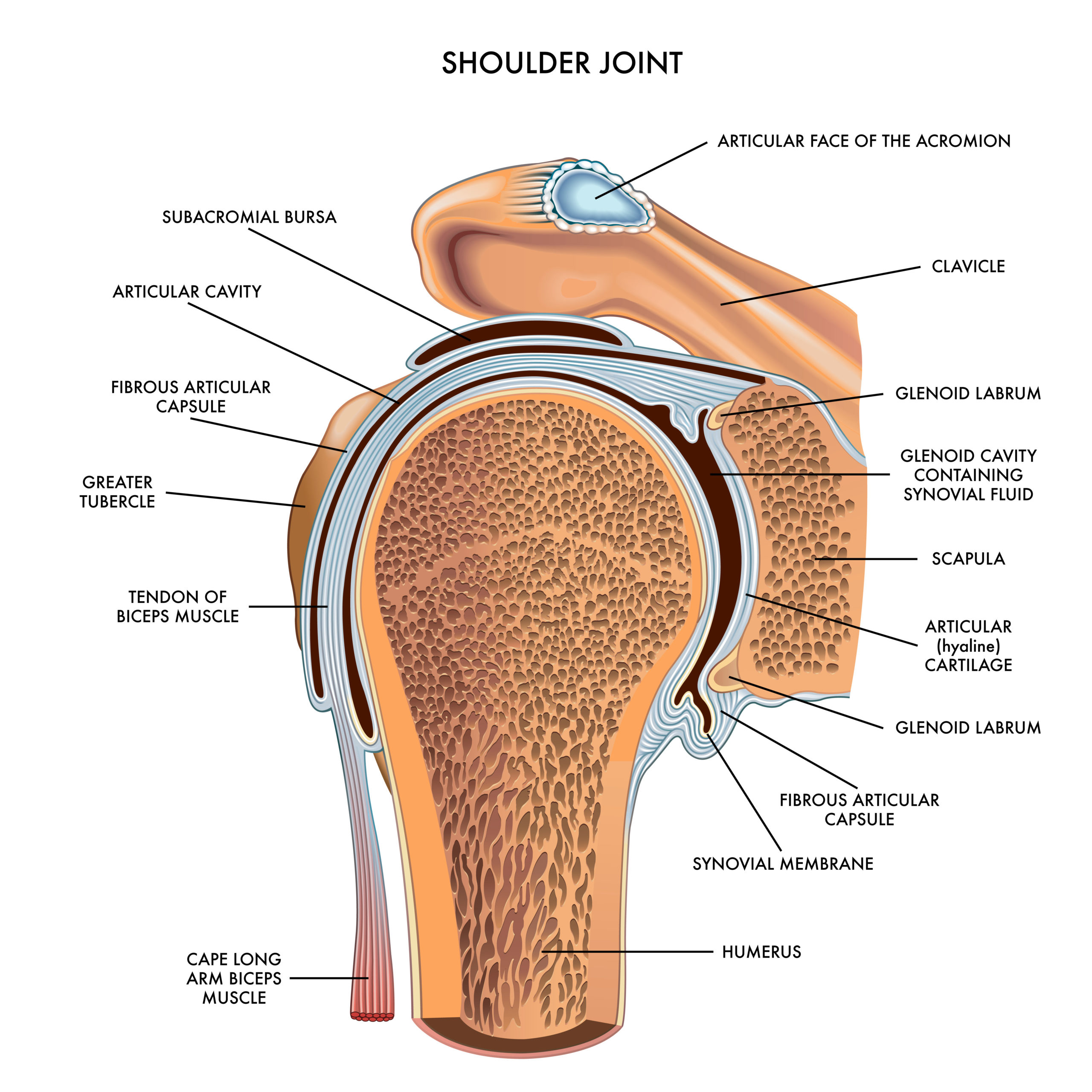

The shoulder joint is a ball and socket joint that connects the bone of the upper arm (humerus) with the shoulder blade (scapula). The capsule is a broad ligament that surrounds and stabilizes the joint. The shoulder joint is moved and stabilized by the rotator cuff. The rotator cuff is comprised of 4 muscles and their tendons that attach from the scapula to the humerus. The rotator cuff tendons (subscapularis supraspinatus, infraspinatus, and teres minor) cover the shoulder joint and capsule from front, over the top, and around the back. The muscles of the rotator cuff help stabilize the shoulder and enable you to lift your arm, reach overhead, and take part in activities such as throwing, swimming, and other sports such as tennis.

The biceps is muscle is a large power muscle in anterior part of your arm. It serves 2 functions: flexing the elbow such as a biceps curl exercise. The other, perhaps more important function is to help perform power forearm rotation such as when you twist a screwdriver. Distally, the biceps has one attachment at the forearm level across the elbow joint. There are 2 proximal attachments for the biceps. One attachment is a broad thick tendon attachment onto the coracoid process, the anterior bony prominence you can feel just medial to the shoulder joint. This attachment is very strong and rarely rutpures. The other attachment, know as the long head of the biceps, inserts onto the superior labrum inside of the shoulder joint. This attachment is less resilient than the the stronger coracoid attachment and is more susceptible to injury and degeneration.

The biceps tendon can suffer an acute injury or experience degenerative changes over time. Most often, these pathologies can occur at either the distal insertion on the forearm or at the level of the long head of the biceps tendon.

Traumatic injury usually results in rupture of the biceps tendon, causing acute pain, bruising, loss of strength, and muscle deformity in the arm. The mechanism of injury is usually an eccentrically applied load to the muscle. An example of this would be lifting a heavy object that doesn’t budge while the muscle fires. Another example is catching a falling box or other heavy object. The muscle flexes the elbow while the weight of the object pulls the arm into extension against the biceps resistance.

Degenerative tearing may be associated with injury but is usually pre-dated with a history of some biceps pain either in the shoulder region or in the elbow region. Generally, the mechanism of injury is not as dramatic as with ruptures of otherwise healthy tendons. Degenerative tendon damage is a normal life process from cumulative stress to the tendon over time. It can occur in the rotator cuff, biceps, achilles, forearm muscles tendons (tennis elbow, golfer’s elbow), and other large muscle(s) that have large tendon attachments prone to repetitive life use. Degenerative tendon damage is called tendinopathy. Tendinopathy leads to gradual weakening of the tendon integrity making it more susceptible to injury. Sometimes this injury leads to partial tears of the tendon whereas other times it can lead to complete ruptures of the tendon.

Distal Biceps Tendon Ruptures

The distal attachment of the biceps is on the radius bone at the radial tuberosity. The radius bone is one of the forearm bones. At the wrist, the radius makes the base of the wrist joint. At the elbow, the radius is a cylindrical bone that allows the forearm to rotate into the palm up and palm down positions. The biceps tendon inserts below the elbow joint on a structure called the radial tuberosity. The biceps attaches to the radial tuberosity in a manner in which it provides power in rotating the forearm palm up. With the palm up, it provides power to flex the elbow. As there is only one distal attachment for the biceps, a rupture of the distal biceps leaves a person with a dramatic loss of strength both in flexion and forearm supination (palm up rotation). A distal biceps rupture should be fixed as soon as possible – this generally means within 2 weeks of injury. There are very few indications for not fixing the biceps tendon. The main reasons include health status that cannot tolerate surgery or the inability of the patient to comply with post surgery restrictions thereby risking the success of surgery. Otherwise, regardless of age, distal biceps tendons should be fixed to restore functional strength and use of the affected arm.

Distal biceps ruptures are generally associated with some kind of eccentric or sudden load applied across the elbow in which the biceps is flexing the elbow and/or supinating the forearm and there is a large enough counter force from an object resisting the biceps. Ruptures are generally an dramatic experience in which the patient experiences a sudden pain, hears or feels a “pop” across the elbow, notices an acute deformity, and develops swelling/bruising in the anterior elbow region. The bruising may be delayed or immediate. The deformity may be immediate or delayed (within a few days). There is generally pain for a short duration (1 week). There is weakness that persists with use of the arm for supination and elbow flexion activities.

Partial Distal Biceps Tendon Tears

A partial tear indicates that there is no complete disruption of the biceps tendon at the radial tuberosity insertion. There is usually no associated deformity or bruising/swelling about the elbow. There is generally acute short lived pain and persistent soreness/weakness about the elbow with forearm supination and elbow flexion activities. If the tear is “minor”, the pain and symptoms will subside over the course of a few weeks. If the symptoms of pain and weakness with use persist beyond 2-3 weeks, then a concern for a more “major” partial tear is raised.

Diagnosing partial biceps tears is a combination of the history taken from the patient which is usually indicative of a mechanism of injury, physical examination which reproduces pain across the biceps with palpation and biceps muscle resistance maneuvers, and sometimes advanced studies such as an elbow MRI.

Treatment of partial distal biceps tears depends upon several factors – the most important of which are patient driven. Patient age, required/desired use of the arm, symptoms experienced, weakness in use, and grade of injury by MRI all play a part in the decision making. A partial tear can be monitored and given time for symptoms to subside before deciding to consider surgery (generally 4-6 weeks).

Partial tears are at higher risk of progressing to a complete tear. Factors that may lead to progression include size of the partial tear, quality of the tendon (is there tendinopathy?), age of the patient, demand in use of the arm, medical co-morbidities of the patient. If a partial tear completes to a full tear, then surgical treatment is recommend within 1-2 weeks to maximize the recovery for the biceps.

If a partial tear remains asymptomatic and does not affect the patient’s quality of life, it can be left and monitored for symptoms. Generally, no restrictions are place on partial tears that are treated conservatively. Guides of use are based on pain, discomfort, and patient confidence in use of the arm.

Surgery for a Distal Biceps Tear (Complete or Partial)

The surgical procedure to repair a distal biceps tear is a reproducible, straightforward, outpatient procedure. The surgery generally takes anywhere from 30-45 minutes to perform. The procedure is done with a combination anesthesia protocol of a regional nerve block +/- sedation or general anesthesia. The surgery is done with the use of an arm tourniquet to limit bleeding and enhance bloodless exposure and visualization of the structures of the elbow during surgery.

The surgical approach is done through a transverse incision in the elbow crease such that the scar heals in a very cosmetic fashion. Rarely, the incision may have to be extended vertically down the volar forearm for exposure – this is sometimes necessary in larger arms. The surgical incision is generally closed with an absorbable suture that dissolves over the course of several weeks.

There are several surgical repair techniques. The most commonly used technique is by docking the tendon into a bone trough created at the insertion point of the tendon on the radial tuberosity. A special high strength suture is weaved through the tendon. The sutures are passed through a small metal button which is passed into or through the radius bone. The button is “flipped” so that it secures against the bone providing a fixed point of support. The sutures are passed through the button in a manner which allows the sutures to slide and be pulled. This advances the tendon into the bone trough created so that the tendon docks into its attachment point. The sutures are then tied and secured to compress the tendon against the bone. This technique has shown to have excellent strength and security compared to other techniques.

Recovery for Distal Biceps Tears

The recovery for a distal biceps repair is generally anywhere from 12-16 weeks back to full use. Very strenuous labor intensive activities may take 5-6 months for full recovery. The biceps tendon is generally considered healed at 3-4 months.

Immediately after surgery, most patient will go him in a long splint that protects the repair. Patients are generally seen one week post surgery for evaluation. Depending upon the quality of the tissue and the tightness of the repair, the patient may be protected for a longer period of time in a brace of splint. Home exercises are generally started at 1-2 weeks post surgery for protected motion. These exercises are taught to you by your surgical team at your post surgery visit. Some patient may require early therapy right away.

For the first 6 weeks, there is no weight or stress applied to the operated arm. A limit of 1-2 pounds maximum is the restriction for the surgically operated arm. The brace is worn at all times except to perform the therapy exercises taught. If the patient is doing well at 6 weeks post surgery with recovery of motion, gentle muscle loading exercises are taught.

At 6 weeks post surgery, formal physical therapy is initiated if the patient continues to struggle with range of motion recovery.

At 10-12 weeks, the muscle loading exercises are gradually advanced towards full activities of daily living use.

Strenuous loading is achieved anywhere from 4-6 months depending upon the nature of activity required and/or desired.

Outcomes for Distal Biceps Repair Surgery

The outcomes of distal biceps tendon repair are very good. Most patient report recovery of nearly if not all functional strength, excellent pain relief, and near if not full recovery of motion.

In circumstances that the distal biceps tendon has to be augmented with a graft due to poor tendon quality or a graft is required to bridge the distance to the insertion due to delayed repair and tightening of the muscle which does not allows tendon to reach the bone, the outcomes can be good but cannot be guaranteed to be very good/excellent. For this reason, surgical repair is recommended within 1-2 weeks of complete rupture with the hope that such grafts are not needed and a primary repair can be accomplished.

Long Head of the Biceps Rupture

The treatment for injuries and issues involving the long head of the biceps tendon are very different than that for a distal biceps injury. The proximal part of the biceps has 2 attachments. One is a very strong and resilient attachment to the coracoid process of the scapula. The other is the weaker and less resilient attachment inside of the shoulder joint at the superior labrum of the glenoid. The coracoid attachment is rarely involved in injury or suffers degenerative damage that causes pain.

The long head of the biceps is often regarded as the “weakest link” of the shoulder complex as it is often responsible for shoulder pain either from injury or from degenerative changes over time.

Anatomy of the Long Head of the Biceps

The tendon of the long head of the biceps muscle is a tubular, relatively avascular structure, that runs under the pectoralis muscle, through a fibrous sheath made of the superficial fibers of the anterior rotator cuff muscle (subscapularis), between the greater and lesser tuberosities, through the rotator interval (the capsular structure between the supraspinatus and subscapularis), over the humeral head, and becomes confluent with the superior labrum of the glenoid. This circuitous pathway lends itself to multiple points of impingement, incarceration, or damage to the long head of the biceps tendon.

Sites of damage to the long head of the biceps tendon include:

- At the superior labrum resulting in what is known as a SLAP tear/lesion

- Over the humeral head in the avascular zone of the biceps causing tendinosis, fraying or a split tear of the long head of the biceps tendon.

- In the intertubercular groove, causing tendinosis, fraying, or a split tear of the biceps tendon.

The mechanism of damage can be acute and traumatic or can be chronic, progressive, and degenerative in nature. It can also be a combination of both an acute injury and underlying degenerative changes to the biceps tendon.

Symptoms of Long Head of the Biceps Pathology

Symptoms include aching, throbbing pain in the anterior shoulder. Pain with overhead reaching, overhead lifting, rotating the shoulder, and reaching behind the back. Patients often complain of decreased strength and pain with reaching back in the throwing motion, and with release of the ball in throwing. Occasionally, patients will report a popping sensation inside of the shoulder that may or may not cause pain. Other complaints include pain with lifting with the shoulder at the side and any other activation or resistance applied to the biceps.

Acute injuries often involve lifting activities, throwing activities, overhead sports, or falls either directly onto the shoulder or outstretched arm. In an acute injury, there is often shoulder pain that limits use for several weeks. Thereafter, there is a nagging deep joint pain and discomfort with overhead use and lifting. There is occasionally painful popping in the shoulder with overhead shoulder rotation.

Degenerative tears can be aggravated by injury and become symptomatic acutely or over time. Nontraumatic biceps tears generally start as intermittent pain that progresses to constant pain over time. The pain is usually associated with lifting or overhead activities such as throwing or overhead rotation.

Treatment of Long Head of the Biceps Tears

Unlike distal biceps tendon tears, the long head of the biceps is rarely operated on for complete ruptures. This is part due to the fact that there is a second attachment proximally for the biceps. The second reason that surgery is not generally indicated is that the outcomes of proximal biceps tenodesis for ruptures of the long head of the biceps do not fair as well as distal biceps repairs. Failure rates are generally higher and rates of re-tear is higher due to the less resilient nature of the long biceps tendon. It is common to accept the deformity of the biceps with a long head rupture as there is generally little loss of strength.

Nonsurgical Treatment for Long Head of the Biceps Pathologies

For incomplete tears, tendinopathy, superior labrum tears, or split tears of the biceps without complete rupture, nonsurgical treatment can provide pain relief and restoration of function. Conservative treatments can include therapy, cortisone injections, PRP injections, and use of NSAIDS, ice, and other modalities for acute flares.

When nonsurgical treatment fails, surgical treatment can be considered.

Surgical Treatment for Long Head of the Biceps Pathologies

Surgical treatment for partial biceps tendon tears, tendinopathy, some superior labrum tears, and split tears of the biceps is often a procedure called a biceps tenodesis. A biceps tenodesis procedure is when the biceps tendon is detached from the labral attachment inside of the shoulder joint and reattached along the pathway onto the arm bone above or just below the pectoralis muscle attachment. This allows the biceps to remain at length to preserve visual aesthetics of the muscle.

Another surgical option for severely damaged long head of biceps tendons is to perform a tenotomy procedure. The tenotomy is when the biceps is cut from its attachment and allowed to “surgically tear” thereby creating a muscle deformity of the biceps as if it had ruptures spontaneously.

Both procedures have positive benefits of relieving pain. Both procedures can still leave patients with persistent pain although generally somewhat less than prior to the procedure.

Both biceps tenodesis or tenotomy can be done either arthroscopically or via a small open surgical scar in the front of the shoulder. Sometimes a combination approach is used depending upon the nature of the bicep tendon damage as it may dictate the most reliable operative procedure to perform, especially for a tenodesis procedure

Surgical Recovery of Long Head of the Biceps Tendon Surgeries.

Generally, the post surgery recovery is approximately 12-16 weeks back to full unrestricted use. The first 6 weeks post surgery are focused on gentle use for activities of daily living with a 1-2 pound restriction on the arm for weight. Thereafter, gradual weight loading is allowed to the arm until the patient is pain free with full use – normally 12-16 weeks.

Factors Affecting Healing and Outcomes after Surgery

Many factors determine the healing and end outcome of surgical repair after rotator cuff tear. These factors include:

- Age of patient

- Associated findings of rotator cuff degenerative tendinopathy

- Quality of the Rotator cuff tendon

- Medical Co-morbidities: Diabetes, Obesity, Kidney disease, Liver disease, etc.

- Smoking